The sudden announcement that General Motors will stop making cars in Oshawa, Ont., after next year sent shockwaves through the industry on Monday. The impact of GM’s move could extend far beyond the borders of the community east of Toronto that has been synonymous with auto manufacturing for the past 65 years.

- Ford turns away from making cars to focus on trucks and SUVs

- GM to ramp up Equinox production in Mexico, Unifor says

Joe McCabe, CEO of Pennsylvania-based consultancy Auto Forecast Solutions, said the news caught him slightly by surprise, even if he’s had concerns over the plant’s future for the past number of years.

In its heyday, the Oshawa facility produced almost a million cars a year. Multiple shifts of workers used to crank out more than one type of vehicle every day when the plant was operating at full capacity.

The GM plant in Oshawa losing production of the Camaro was a sign of trouble ahead, Charlotte Yates said. (Frank Gunn/Canadian Press)

But in recent years, output has been limited to two gas-powered sedans (the Chevrolet Impala and Cadillac XTS) along with putting finishing touches on two trucks — the GMC Sierra and Chevy Silverado — that came up to Canada after being primarily built at a plant in Fort Wayne, Ind.

McCabe said Oshawa was mainly producing “orphan products” — vehicle types that the company doesn’t really want to keep making.

ANALYSISChinese electric cars are coming to Canada, but you can’t have one yet: Don Pittis

Auto tariffs would be ‘catastrophic’ to Canada and cost 100,000 jobs, dealers warn

It was buried in Canada by the Oshawa news, but GM also announced it will stop making a number of car models entirely, primarily gas-powered sedans that are no longer selling much and aren’t very profitable even when they do.

By the time the changes are fully implemented, GM plans to reduce its global workforce by about 15 per cent. And the company said three quarters of its sales will come from just five different types of cars.

Capitalism keeps thwarting the critics, this time U.S. giant carmaker GM releases the Chevy Bolt with an electric range of nearly 400 kilometers. (General Motors)

It’s part of a push by GM to invest in places it thinks can make more money — electric, autonomous vehicles, and larger trucks and SUVs with high profit margins.

“When you look at a crossover, or an SUV, or a light truck, they are highly profitable vehicles for these manufacturers,” McCabe said. “It’s more beneficial for them from a financial standpoint to build what the consumer wants.”

One of the Oshawa plant’s biggest selling points was the flexibility of its assembly line, making it more nimble and attractive as a place to produce future models. While GM could theoretically have rejigged the plant to build different types of cars, that didn’t happen because the company has enough under-used factories elsewhere.

‘Think long term’: Former Toyota boss says Canada can’t lose its car plants

ANALYSISGM plan to hire up to 1,000 engineers in Canada a major boost for self-driving car’s future

“There’s really no product to retool it for,” McCabe said. “They’d just be shipping from another underutilized plant [and] it would leave them with two.”

Independent automotive analyst Jon Gabrielsen said the Oshawa plant fell victim to forces that are impacting the entire industry.

He notes that the company didn’t just drop the axe on Oshawa, but also singled out two assembly plants in Detroit and Ohio, along with two propulsion plants in Maryland and Michigan.

Ford moving all small car production to Mexico from U.S.

The Detroit-Hamtramck Assembly plant also makes the Impala, “and they’re closing it too,” Gabrielsen notes. The closure of the Hamtramck facility is significant because it’s GM’s last car assembly plant in Detroit — a city even more associated with automaking than Oshawa.

“If they had only cut Oshawa I would say we should expect more shoes to fall because that’s not enough to realign your footprint,” Gabrielsen said. “They think they’re done now.”

Charlotte Yates, principal investigator at McMaster University’s Automotive Policy Research Centre, said the last round of negotiations with GM’s union were the first hint that the Oshawa plant faced trouble. The company refused to commit to a new product for the plant, after moving Chevy Camaro production.

Charlotte Yates, principal investigator at McMaster University’s Automotive Policy Research Centre, said the last round of negotiations with GM’s union were the first hint that the Oshawa plant faced trouble. The company refused to commit to a new product for the plant, after moving Chevy Camaro production.

“That suggested [Oshawa] wasn’t part of the long term plan,” she said.

The loss of GM’s presence in Oshawa, if it comes to pass, will reverberate through Canada’s entire economy, but the impact will be most acute locally. “That plant is like the centre of a manufacturing ecosystem,” she said. “[It’s an] anchor of the economy [so] with that gone it’s a real disruption.”

Reason for optimism?

That’s not to suggest the industry in Canada is now doomed.

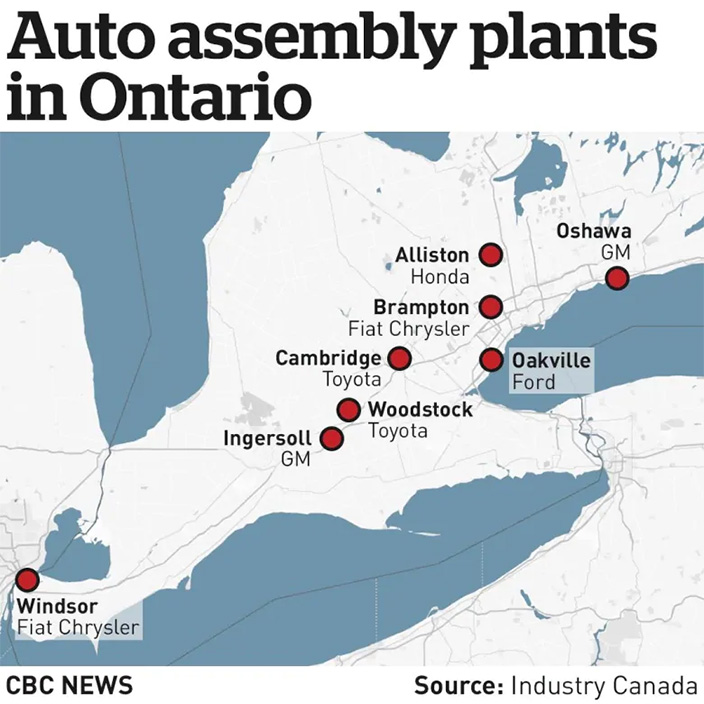

Oshawa may be the Canadian city most associated with auto making, but many others have major parts or assembly plants and their futures aren’t looking quite as bleak.

(Scott Galley/CBC)

Ford’s assembly plant in Oakville, Ont., should be safe, Gabrielsen suggests “because it makes SUVs which Ford is keeping.” And GM also runs the CAMI plant in Ingersoll, Ont., where it makes the Equinox, another SUV.

“That’s right in the middle of the type of vehicles that they feel consumers are moving towards for the next five years,” he said, calling the plant’s future “pretty safe.”

Beyond the car companies themselves, Canada is home to a cornucopia of auto parts firms, most of whom are members of the Auto Parts Manufacturers’ Association, led by Flavio Volpe.

GM alone spends $3 billion a year on parts and tools from suppliers across Ontario, Volpe said, money that supports thousands of jobs beyond those working for GM itself.

GM “deciding there may not be a path forward in the Toronto region is going to be felt across the country,” he said. Areas of the industry that have gotten the most investment in recent years include anything to do with autonomous vehicles and electric-powered cars.

Barely two years ago, GM announced plans to hire up to 1,000 engineers at a new facility in Markham, Ont. to work on software that will control self-driving cars.

Volpe said Canada has the right mix of companies and skilled workers to see more investments like that — moves that can filter down to assembly line workers, too.

Regardless of what advanced technology those next generation cars have under the hood, “they still have doors, and windows, and engines and body panels,” Volpe said. “Somebody’s got to make them.”

While Canada still has a role to play as a link on the North American automotive supply chain, Gabrielsen said Monday’s news from GM should serve as a warning to anyone associated with the industry. Other companies may soon “have to make the same type of decisions which may or may not impact Canada,” he said.

For now, his advice to Canadian car workers is blunt: Even if you don’t work for GM, “you need to worry.”

Indo Canadian News News That Matters

Indo Canadian News News That Matters